Once there was a killer in nearby Austin who was still at large. He had chloroformed his victim (rather humanely, I thought) before chopping her head off with an axe. Fear that ‘dat debblish axe-man’ might strike again, in only the Lord knew whose house, resulted in some extraordinary precautions. From the morning Pinkie heard about the axe-man’s method of operation until the day that he was finally trapped — a period of three weeks — she and Annie (her mother) kept full tubs of water inside their front and back doors and in front of the fireplace. The water, Pinkie explained, would absorb the chloroform in the event the axe-man shot it squirt-gun fashion through the keyholes or down the chimney. Just to be on the safe side, though, Pinkie confided, ‘Annie, she sets up half de night, and me, I sets up tother.’ (1)

This account of the servant girl murders was told to Edna Turley Carpenter (1872-1965) by her friend Pinkie Sorrel Bonner (1881-1940), probably before 1900, and re-told by Mrs. Carpenter in her memoirs some 60 years later.

The Austin Axe Man made strong impression on young Pinkie even though she was only a small child in 1885. Although her childhood memories of the events might have been hazy, the account is remarkable for a couple of reasons: the description of the elaborate safeguards taken against a perpetrator believed to be using chloroform; and the belief that the killer had eventually been caught.

If in Pinkie’s memory — the memory of a young black woman from the end of the 19th century — the Austin Axe Man had been caught, it is likely that it was a memory shared among the African-American community at the time. Austin’s black population — which had been significantly impacted by the servant girl murders — more so than the white population — might have been more keenly attuned to the possible identity of the perpetrator, whereas in the white community and in the Austin press, the murders were still described as a mystery years afterwards.

Chloroform had been mentioned as possibly being used in the Vance/Washington murders but was never confirmed by the authorities. I had previously thought the use of chloroform was a far-fetched idea, but I have subsequently come across a number of accounts of its use in crimes, especially robberies, during the 19th century. It was frequently used to disable victims and allow the perpetrator to escape without being detected, or that was the intent, sometimes it didn’t work as planned. Chloroform was hard to administer correctly — it was easy to knock someone out but they often regained consciousness if the dose was not sufficient.

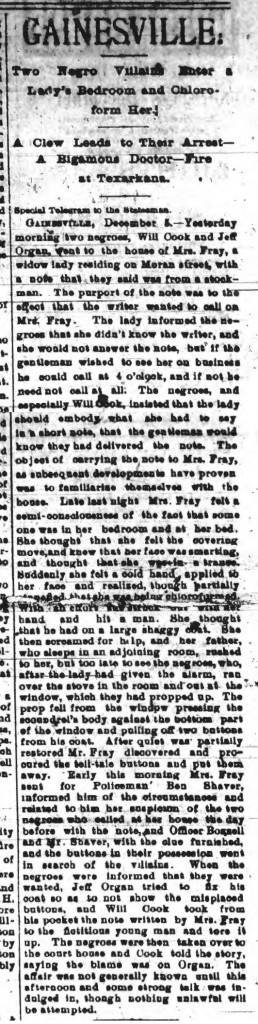

The following account from 1888 took place in Gainesville, Texas (2) where two men entered a house in an attempted robbery and tried to use chloroform to subdue a sleeping woman whose residence they had cased earlier in the day. The woman, “felt a cold hand applied to her face and realized, though partially stupefied, that she was being chloroformed. With an effort she struck out with her hand and hit a man.”(3) This story is typical, the victims were frequently female, the perpetrators were usually seeking an easy target and an easy escape rather than a violent confrontation. In this instance they were chased off and later apprehended.

———————–

(1) Carpenter, Edna. Tales from the Manchaca Hills. New Orleans : Hauser Press, 1960. p.186

(2) A double axe-murder was committed in Gainesville, Texas in July 1887 that was so similar to the Austin murders many were convinced it was the work of the same perpetrator.

(3) 6 December 1888. Austin Daily Statesman.