About The Victims

It has been my intent since I started this website to provide some biographical information about the victims of the murders since there was scant information about them in the original newspaper articles. Most of the victims would have most likely lived their lives in historical anonymity had this tragedy not happened.

The task of finding biographical information about the victims is difficult for two reasons: one, the irregular nature of recordkeeping and record preservation in Texas in the late 19th century; and two, women and persons of color were disproportionately underrepresented and underdocumented in the public record compared with property-owning males. Nevertheless I have tried to gather the information that is available in the public record and present it here, incomplete and fragmented though it may be.

The murders of 1885 created a window, although a shattered window, into the lives of these women in that place in time. We can pick up the pieces and try to construct a portrait of what their lives were like: They raised families, worked in their communities, and were remembered by those who loved them, their children and their children’s children, until being inevitably forgotten by far flung descendants.

I consider this a work in progress and hopefully I can make updates to it in the future.

Mollie Smith

She was a light-colored mulatto, apparently about twenty-five years of age.

…not married…

[She] had been in the service of the family as a cook for a little over a month.

The deceased woman possessed a high temper, and she had once spoken of nearly killing a man with a bottle.1

These four lines comprise the entirety of the newspaper’s description of Mollie Smith. They also illustrate the frequent signifiers applied to women of color at that time, especially the specificity regarding their racial categorization and temperament.

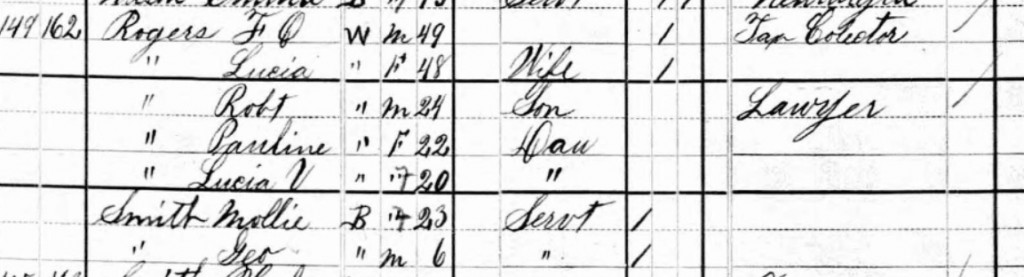

Mollie Smith, like many other persons in 1880s Austin, came from somewhere else. She was born in Virginia in 1857, was in Texas by the early 1870s if not sooner, and first appears on the US Census in Waco, Texas, working as a domestic servant at the residence of Friend Ovid Rogers (1830-1905), the county tax collector. The Rogers household included a wife, two daughters and a son, Robert, a lawyer, who was the same age as Mollie.2

Domestic servants, especially young women employed as such, seemed to change employment with some frequency, depending upon a variety of factors.

Mollie Smith evidently moved back and forth between Waco and Austin a couple of times in the early 1880s; she is listed in the Austin City Directory more than once during that time period; but Walter Spencer, a boyfriend, stated that he knew her in Waco during the same time period. At the time of her death she was working at the residence of Walter Hall on West Pecan Street (6th Street) just past Shoal Creek. A few months prior she had worked at the home of Frank Woodburn on Chestnut Street (18th Street) just south of the University.3

One important detail missed by the newspapers was that Mollie had a ten-year-old son, George.

His exclusion raises several questions. Was George separated from Mollie and if so, why? Was George merely overlooked by the newspaper? And what became of him after her death?

The newspaper reporter covering the crime left no stone unturned, detailing everyone in the household and their relation to the deceased. In the later murders the children of the deceased were always mentioned. This exclusion seems to indicate that George was not with his mother during that fateful December in Austin. The absence of George with his mother in Austin is exceptional – in every instance of the murders, the children were always residing with their mothers at the residences where they worked.

I think it is within the realm of possibility that George Smith might have been the son of Robert Rogers, based on the fact that George was not with Mollie in Austin at the end of 1884 and was instead being kept with the Rogers family. Mollie was also listed as being single in the 1880 census, rather than divorced or widowed.

***

George Smith is a common name and 11-year-old George would be very difficult to track down in the historical record with any accuracy without supplemental uniquely identifying details.

There is a George Smith listed in the 1900 census living in Waco, who is the correct age (26); occupation noted as lawyer; race listed as white; parents listed as unknown.4

There are three African American George Smiths listed as living in Austin in the early 20th century. Two are close to the correct age, the other is unknown.

Whether any of the George Smiths in Austin, or any other George Smith in Texas, were the orphaned son of the servant girl Mollie Smith would be difficult to determine; but I would like to take the opportunity to briefly note them since they were in Austin at that time (circa 1900).

- George W. Smith worked as a maintenance man at the Deaf and Dumb Asylum. He was married in Austin; had a son and daughter; he and his family eventually moved to Chicago where he worked as a maintenance man at a hospital there. Interestingly, while living in Austin his race was recorded as “black” in the Travis County Census; ten years later in Chicago, his race was recorded as “mulatto”; twenty years later in the subsequent US Census his race was recorded as “white” and his then adult son’s occupation was recorded as Chicago police officer.5

- George H. Smith worked as a porter at various retail businesses in Austin including the Driskill hotel; he was married and lived in East Austin.6

- Rev. George E. Smith, pastor of the Apostolic Church of God; he was married and lived on Rosewood Avenue in East Austin.7

***

Whatever happened to young George after his mother’s death, he would have been old enough to remember her; and if he was not in Austin, he was at least spared the memory of her murder.

Eliza Shelley

…a colored woman named Eliza Shelley, and her three small children. The woman was employed by him [Dr. Lucien B. Johnson] as a cook, and had been in the service of the family a long time.

…the woman had no money, unless a few paltry cents, that she might have saved from her wages.

Eliza had formerly lived in the country, where she also was in his service, and was an excellent woman. She had a husband in the penitentiary, to whom she was greatly attached.

The Doctor’s wife [Ruth] also testified to the good character of the deceased. The murdered woman was about thirty years old, of medium size, and of unmixed African blood.8

The Austin Daily Statesman portrayed Eliza Shelley in a positive light, remarking on her good character, temperament and steadfastness; a faithful wife, mother and employee.

There are several discrepancies between the various sources for information about Eliza Shelley. According to the US Census, Eliza Shelley was born in Texas in 1857. In 1880 she was living in McLennan County, Texas and was the mother of two children, Georgia, a daughter, aged 7, and an unnamed son, aged 6 months. At the time of her death, the newspaper reported that she had three boys.9

The newspaper also reported that she had been working for the Johnson family for some time, however the 1880 US Census lists Dr. Lucien Johnson and his wife living in rural Travis County (rather than in Austin). A 23-year-old, white, female servant is also listed as being employed by the family. Eliza was not listed with the Johnsons at that time. And the 1885 Austin City Directory listed Eliza as residing in a “colored” boarding house of East Ash Street.10

By 1885 Lucien Johnson and family had moved to Austin. Eliza Shelley was murdered at their home on Cypress Street on the night of May 7, 1885.11

Ike Shelley, a prisoner in Huntsville, Texas in 1880, was likely Eliza’s husband. He was incarcerated in 1879 and released November, 1885.12

***

“Shelley” is a very rare surname among African Americans in Texas during that time period, and the few that show up in the public record are hard to trace. Three possible descendants of Eliza include:

- Oscar Shelly, the only African American named Shelley in Austin in the early 20th century. Oscar was born approximately 1879; he is in the Austin City Directory in 1906; he turns up again in the 1920 Travis County Census as the owner of a home on Rosewood Avenue with his wife, Marguerita.13

- Thornton Shelley, born Travis County 1879, mother Eliza Johnson; father William Shelley. He died 1953 in Somerville, Texas.14

- Georgia Shelley, living in San Angelo, Texas, 1944.15

None of these individuals turn up reliably or consistently in the US Census or other public records in the early 20th century and it would be hard to determine if they were related to Eliza Shelley, but I thought they were worth noting for the genealogical possibilities.

Irene Cross

…a colored woman named Irene Cross, living in the yard of Mrs. Whitman,…

The house in which she lived had two apartments; in one of them slept a small boy, a nephew of the woman, and the other was occupied by her grown son and self.16

Irene Cross was born in Mississippi, about 1847. By 1870 Irene and husband Haywood Cross were living in Austin, along with their 9-year-old son Washington.17

By 1880 Irene Cross was widowed, her husband having died sometime in the 1870s. Irene lived on Chestnut Street (now 18th Street) with her son, Washington and an 8-year-old nephew, Douglas Brown.18

In 1885 she was living on Linden Street, across the from Scholz Garden; Washington and Douglas were still living with her. She was murdered there the night of May 23, 1885.19

The night Irene was murdered, Washington was gone, but Douglas was there; he was one of the few people to see the killer whom he described as a, “big, chunky negro man, bare-footed and with his pants rolled up.”20

Irene Cross, like Mollie Smith and Eliza Shelley, was buried in the colored section of Oakwood Cemetery.21

***

Washington Cross continued to live in Austin; he married twice, first to Macky Brown with whom he had one child, Estella Cross, in 1888. He later married Nancy Spence in 1892. There is no trace of what happened to Nancy Spence although Washington Cross lived next door to a Spence family in Austin in 1910.22

Washington Cross is listed in the city directory as late as 1918; there are no records of his death.23

Irene Cross’s granddaughter, Estella Cross married Eugene Armstrong, a horse trainer. Eugene died of tuberculosis in 1917. They did not have children. Estella lived in Austin the rest of her life, she died in 1967 and is buried in Evergreen Cemetery.24

Mary Ramey

…a colored child

…11 year old daughter25

Mary Ramey wan born in Austin in 1875. She never knew her father, Jacob Ramey; he had died several months before she was born.26

Mary was raised by her mother, Rebecca Ramey, and grew up in a family which included an older brother and sister, a grandmother Harriet Carrington and an uncle Edward H. Carrington, who had opened the Carrington grocery store on East Pecan Street (6th Street) in 1872 and which was one of the first African American-owned businesses in Austin.27

The grocery store was also home to the Carrington and Ramey families — downtown merchants often lived on the property from which they conducted their businesses and the Carrington family did so in the early years of their business.

Growing up on Pecan Street, experiencing the sights and sounds of a busy but friendly neighborhood, Mary Ramey would have been known and loved by family and friends and neighbors, including an uncle who ran a blacksmith shop next door. She would have been the baby of the family, the center of attention who greeted regular customers and folks from the neighborhood who stopped in the store for lunch. Her mother would have told her to stay out of the busy street and to stay away from the streetcar tracks and not to wander into the lumber yard behind the store and not to fall into Waller Creek just to the east. As Mary grew up she would have followed her brother and sister to Central Grammar School; she would have made friends with children in the neighborhoods along Red River Street and East Avenue, where at that time, many African American families made their homes.28

Growing up on Pecan Street, experiencing the sights and sounds of a busy but friendly neighborhood, Mary Ramey would have been known and loved by family and friends and neighbors, including an uncle who ran a blacksmith shop next door. She would have been the baby of the family, the center of attention who greeted regular customers and folks from the neighborhood who stopped in the store for lunch. Her mother would have told her to stay out of the busy street and to stay away from the streetcar tracks and not to wander into the lumber yard behind the store and not to fall into Waller Creek just to the east. As Mary grew up she would have followed her brother and sister to Central Grammar School; she would have made friends with children in the neighborhoods along Red River Street and East Avenue, where at that time, many African American families made their homes.28

By the mid-1880s Edward Carrington had apparently sold or leased the store on Pecan Street to Richard Dukes and had re-located his own business to Mesquite Street (11th Street) a few blocks north. Rebecca Ramey found employment working as a domestic servant at the residence of Valentine O. Weed on East Cedar Street (4th Street) and she and Mary lived on the property. On the night of August 31, 1885, an intruder entered Rebecca Ramey’s bedroom, knocked her unconscious and then took Mary into the backyard where he raped and murdered her.29

***

After the death of her daughter, Rebecca Ramey moved to East Austin neighborhood of Rosewood where she lived for the rest of her life with her older daughter Minnie and son-in-law Lee Green.30 An 1888 newspaper article stated that Rebecca had “never recovered from the shock and the wounds of that terrible night of blood.”

By 1885, Mary Ramey’s surviving siblings, Edward (1869 – 1888) and Minnie (b. 1870) were old enough to have found gainful employment and were living independently. Edward married Janette Lindsey in 1887. He worked as a clerk at Duke’s Grocery, formerly Carrington’s and then as a porter at the Iron Front saloon where he was killed in an electrical accident in 1888. Minnie Ramey married Lee Green in 1895.31

By 1900, Edward H. Carrington had moved back into the grocery store on East Pecan and he continued to operate it until 1907 when his son-in-law, Louis D. Lyons took over. Edward Carrington, was an influential leader in Austin’s African American community; he loaned money to families in need and his business served as an informal community center. His family continued his efforts to serve Austin’s African American community after his death in 1919.32

Edward H. Carrington had four daughters, one of them named after his sister, Rebecca. The Carrington daughters married, had families and still have numerous descendants living across the United States.33

Rebecca Ramey died in Austin in February, 1909. Her daughter Minnie died three months after her in May, 1909. Rebecca has no living descendants that I am aware of.34

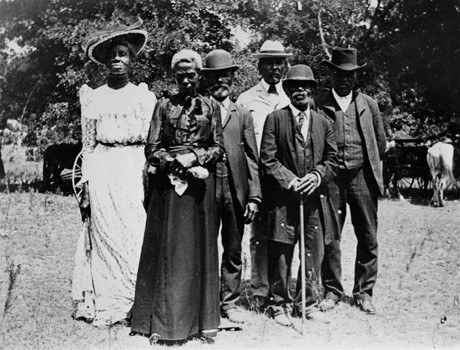

Mary Ramey’s uncle, Edward H. Carrington on far right. PICA 05476 Austin History Center, Austin Public Library.

Gracie Vance & Orange Washington

…a man and a wife, two colored people, known as Gracie Vance and Orange Washington.

…mulatto wife or mistress

…his so-called wife Gracie Vance

Gracie Vance (sometimes called Washington)…

…the girl Gracie was living with Orange Washington without resorting to the formality of legal marriage

…Orange whipping Gracie — an act that he had been frequently guilty of. 35

In 1885, Orange Washington was employed by Michael Butler, an Austin builder. Orange rented a small cabin on the property of William Dunham at 2408 Guadalupe Street and Gracie Vance lived there with him. They were both murdered there the night of September 28, 1885.36

***

Orange Washington was the oldest son of George and Mary Washington, originally from Virginia. By 1870 the Washingtons were living in Brenham, Texas working on a farm with four children including Orange.37

***

Gracie Vance was daughter of Eliza and Charles Vance. Gracie was born in Texas in 1865. She was briefly married to Albert Hall, a Masontown railroad worker, before she met Washington.38

Gracie’s mother, Eliza Vance was born in Tennessee in 1842. Eliza Vance lived in Austin with her son James and his wife Julia through at least 1914. Eliza worked as a washerwoman into her 70s; she likely died about 1920.39

Susan Hancock

…a white lady, the wife of Mr. M. H. Hancock… 40

Susan C. Hancock was born Susan Clementine Scaggs, in Alabama in 1840. I have not been able to find her parents or immediate family apart from a twin sister, Martha Fallwell, and a brother William T. Scaggs.41

Her husband, Moses H. Hancock was born in North Carolina in 1830. By 1860 he was living in Bonham, Texas, working as a carpenter.42

During the Civil War Moses Hancock served in Howell’s Battery and the Eleventh Texas Field Artillery from Fannin County, Texas.43

Susan married Moses Hancock about 1868. By 1870 the Hancocks were living near Brenham, Texas and they had a daughter, Lena. Moses still worked as a carpenter. Susan’s sister Martha Fallwell and her husband were their neighbors.44

By 1880 the Hancock and the Fallwell families had moved to Waco, where they again were neighbors. The Hancocks also had another daughter by this time, Ida.45

Sometime between 1880 and 1884, the Hancocks moved to San Antonio without the Fallwells. They then moved to Austin in early 1885. Moses likely hoped for carpentry work in Austin, which at that time was experiencing a construction and housing boom. They purchased a home on Water Street in the southern part of the city, just north of the Colorado River.

On the night of December 24, 1885, an intruder entered the Hancock home. Lena and Ida Hancock had gone to a Christmas party and were not at home that night. Susan Hancock was asleep in her daughter’s bed when an intruder struck her in the head knocking her unconscious before carrying her into the backyard. Moses Hancock woke up when he heard a noise and was able to scare the intruder off. Susan Hancock was severely wounded; she survived three days and died on December 28, 1885.46

***

After the murder of Susan Hancock the Hancock family was pulled apart.

Suspicion fell upon Moses, and he was arrested for murder. Moses found an unexpected advocate in John Hancock, who thought the case against Moses was dubious and defended him pro bono and the case against him was dropped. However, through a complicated series of efforts on the part of his brother-in-law, William Scaggs and the proddings of private detectives, Moses was later re-arrested, charged, indicted and tried for Susan’s murder.47

In court testimony William Scaggs and his wife stated that Moses was a drunk and abusive husband who had made threats against his wife. Susan Hancock’s sister, Martha Fallwell’s relationship to Moses was not as bad as the Scaggs, but she did paint a somewhat unflattering portrait of her brother-in-law, stating that Moses never mistreated Susan, except cursing her when he was drunk, and that Susan was afraid of any drunk man.48

16-year-old Lena Hancock defended her father, testifying that “Papa always treated mama kindly, and never whipped us girls in our lives.”49

Susan Hancock had thought about leaving her husband and at one point and had written a letter detailing her reasons for leaving.

Dear Husband: I have lived with you 18 years and have always tried to make you a good wife and help you all I could. I have loved you and followed you day and night. You won’t quit whiskey, and I am so nervous I can’t stand it, you know, it almost kills me for you to drink, and Lena is almost crazy and will lose her mind. If I was to do anything to disgrace you and our children, you would leave me, you would have quit me long ago.

Take good care of yourself. Write to me at Waco, and I will answer every letter.

Your wife until death,

Sue Hancock

Susan never went through with her plans to leave Moses but she kept the letter hidden away and it was later found among her belongings after her death.50

***

After the death of his wife, Moses Hancock was his own worst enemy. He was drinking heavily, he was threatening and abusive to his in-laws and various others; he made up strange stories and accusations related to the murder and talked about leaving the country. In spite of himself he was ultimately exonerated of Susan’s murder in 1887.51

Moses Hancock remained in close proximity to his daughters when possible, eventually moving in with Lena, who was evidently a devoted daughter, taking in Moses when she lived in Austin and later in Waco, taking care of him until his death at the age of 89 in 1919.52

***

In February 1886, 16-year-old Lena married Moses Ramsey. The Ramseys had been neighbors of the Hancocks in Austin. The marriage was short lived however. Moses died of a sudden illness only nine days after his daughter Roxie was born in December 1886. 53

Lena next married Joseph Cerberry in Austin in 1890. They had two daughters, Mary, born 1891 and Maude, born 1894. Joseph drove a beer wagon for Houston Ice & Brewing; Lena took care of their daughters.54

By 1900 the Cerberrys were still married and still in Austin, but Lena Cerberry was then listed in the city directory as running a boarding house at 207 East 9th Street (which coincidentally was the location of the infamous Burt murders of 1896).55

Lena and Joseph were divorced by 1903, but Lena was still in Austin, working as a dressmaker, taking care of her daughters as well as her father, Moses who now lived with them.56

Lena moved to Waco in 1909; she was married two more times, the last husband being a fireman who was 18 years her junior. They moved to Dallas but eventually divorced sometime in the 1930s. Lena lived the rest of her life in Dallas; she died in 1958.57

Lena Hancock has several descendants still living in Texas who remember her as smart generous woman, with a great fondness for animals, especially dogs, and I have been told that Lena always kept several large dogs around the house, as well as what was described as a vicious parrot that guarded the house. She never spoke to her descendants about what happened to her mother.58 Although, if Lena had been home that Christmas Eve night and if she had been asleep in her bed instead of her mother, she would have most likely been killed instead.

***

After her mother’s death, Ida Hancock lived with the Fallwells in Waco until she returned to Austin with them in 1887. She married Ashley Cooper, an Irishman, in Austin in 1894. Cooper worked as a typesetter for the Austin Dispatch and later the Austin Daily Statesman. Ida and Ashley Cooper left Austin in 1901 and were constantly on the move for a number of years, living in Houston, El Paso, Bisbee, and San Francisco, before settling in Honolulu in 1905. In 1906 Ida left Ashley and moved to Mexico City without him. In 1912 Ashley Cooper, still residing in Honolulu, attempted to serve Ida with divorce papers but the Mexican authorities were unable to locate her and efforts to find her were eventually called off in 1914. 59

***

Susan Hancock’s sister, Martha Fallwell and her husband Elisha, moved to Austin in 1887, and Elisha C. Fallwell served as an Austin police officer for the next ten years.60

Eula Phillips

[She was] the pretty young wife of Mr. James Phillips, Jr.

That she feared him when he was drinking.

[She had] a child, 18 months old…

That she was unfaithful to her marriage vows.61

This is essentially all that the newspapers had to say about Eula; although her “unfaithfulness” was investigated in greater detail in the press and in the courtroom in the weeks after her murder and it dominated the criminal investigation and prosecution of her husband, James.

Eula Phillips was born Eula Burditt on April 22, 1868 to Thomas and Alice Burditt. The Burditts came from a family of early settlers of Travis County and numerous Burditt families farmed and ranched in the area. Likewise, Eula’s mother family, the Eanes, were early settlers in the county and Eula had an extensive number of relatives from her mother’s side of the family living in the area as well.62

By 1870, Thomas, Alice and their two daughters 4-year-old Alma and 2-year-old Eula lived on a farm near Walnut Creek that adjoined that of Alice’s brother, Richard Eanes.63

By 1880 Thomas and Alice had separated; Thomas lived and worked on the farm of his brother, Giles Burditt; Alice and the girls had relocated to southern Travis County, near Onion Creek. Alice taught school in Manchaca.64

In late 1882, Alice filed for divorce from Thomas. However the case never came to trial because in the intervening weeks Alice had died, most likely succumbing to a typhoid epidemic in the Onion Creek area at the time. She was only 36 years old.65

Less than a month later, Eula married 21-year-old James Phillips, Jr. in January 1883.66

***

I would speculate that the marriage of Eula to James Phillips, taking place almost immediately after the death of her mother, was the result of an arranged marriage; and that this sudden series of events — the death of her mother, her subsequent marriage, and the move into a new household with a strange new family — were deeply unsettling to the 14-year-old Eula.

***

James and Eula did not have the means to “go to housekeeping” as James’s mother described it, and the newlyweds moved into the family home of James’s parents on Hickory Street (8th Street) just west on downtown. James Phillips Sr. was a carpenter and builder and he had a small workshop on the property. Eula spent most of 1883 pregnant; she gave birth to a baby boy, named Thomas, after her father, in January 1884. The rest of 1884 evidently passed uneventfully, perhaps she had settled in with being a new mother and the attendant concerns.

In January 1885 James and Eula moved to the farm of George McCutcheon and his family in Williamson County. McCutcheon was a friend of Eula’s father and most likely McCutcheon had offered steady work to James.

The move to the McCutcheon place proved to be ill-fated. McCutcheon’s wife died in March. Later that year, Eula became pregnant by the 36-year-old McCutcheon and he quickly purchased pharmaceuticals to terminate the pregnancy.

In October 1885, James and Eula returned to Austin and again took up residence at his parent’s home. Eula was described as unhappy during this time, sometimes sleeping in the parlor. James was drinking, unemployed and suspicious that his wife was seeing another man.

In the last three months of 1885, Eula and James’s marriage seemed to be unraveling. Eula started having a not-so-discrete affair with 27-year-old John Dickinson. Dickinson was single, attractive, wealthy and well-connected, and he held the prominent position of Secretary of the Capitol Commission, the agency overseeing the construction of the state capitol building then in progress.

In November of 1885, Eula left her husband, taking her infant son with her. She then spent a week at the residence of Fanny Whipple, where she met Dickinson in the evenings. Evidently Eula did not plan on returning to James because she had Mrs. Whipple fetch her belongings from the Phillips home. Eula only stayed at Mrs. Whipple’s a week then moved into the home of May Tobin where she spent the following week, again seeing Dickinson on several occasions. She then left Mrs. Tobin’s and went to Manchaca and Elgin and stayed with relatives.

Both Whipple and Tobin operated what were called “assignation houses;” which were private residences in which the owners rented rooms for romantic encounters and provided a certain amount of discretion to their customers; discretion that would not have been possible if one checked into a local hotel or boarding house.

While Eula was gone, and at the urging of his mother to straighten up, James Phillips stopped drinking, secured a carpentry job, bought some furniture on credit. At the beginning of December, accompanied by his older sister, Dorothy Creary, James traveled to Elgin and convinced Eula to come back to Austin. Eula and Thomas returned to the Phillips home.

All was seemingly quiet at the Phillips household the rest of that month; James was worked on the construction of Fireman’s Hall and Eula and the baby were at home.

On the night of Christmas Eve, after the Phillips household was fast asleep, Eula slipped out of the house and accompanied by someone unknown, arrived at May Tobin’s, where she had previously spent time with John Dickinson. Eula asked Tobin for a room, but none were available and Eula left. Within an hour Eula was dead. May Tobin and whoever accompanied Eula were the last persons to see her alive. 67

***

In my opinion, Eula’s secret Christmas Eve liaison strongly suggests a continuing romantic involvement; one for which she would risk her absence being detected in order to spend whatever time she could to be with her paramour before leaving Austin the next day with her husband.

***

James Phillips Jr., who in spite of being severely injured on the night of his wife’s murder, was subsequently indicted and tried for the murder of Eula and was found guilty. James was portrayed by the prosecution as a violently jealous husband, and claimed that he was motivated by Eula’s infidelities to kill her.68

However, the conviction was subsequently overturned by the Texas Court of Appeals, which stated that the entirety of evidence of Eula Phillips’s infidelity was inadmissible because the prosecution produced no direct evidence that the defendant himself had knowledge of his wife’s infidelity.69

After the ordeal of his trial, James remained in Austin and lived with his parents until 1891 when he married Ida Hart. James and Ida moved to Georgetown, Texas; James worked variously as a farmer, carpenter and music teacher.70

James and Ida went on to raise four children before Ida’s untimely death in 1910 at the age of 41. James Phillips, Jr. died in Georgetown in 1929. James and Ida have numerous descendants still living in Texas.71

***

After the murder of his mother, Thomas Lawrence Phillips was raised by his aunt Dora Allen. George and Dora Allen, Thomas, his father and his grandfather lived in the Phillips home on Hickory Street until it was sold and demolished in 1891. Thomas continued to live in Austin with the Allens until 1906; the city directory lists his occupation as bartender.72

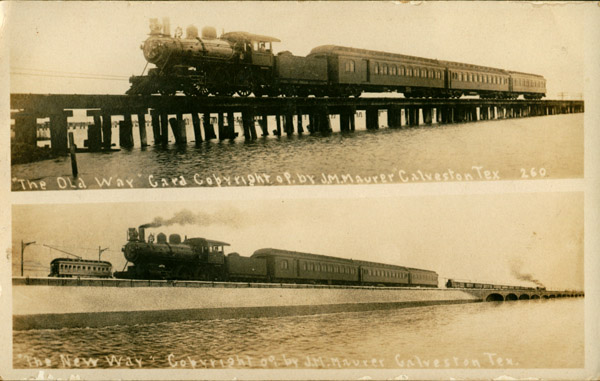

Thomas Phillips moved to Galveston sometime in the early 1910s. He worked as a pile driver for Missouri Iron and Bridge Company, and was most likely involved with the construction of the Galveston Causeway.73

In 1916 Thomas married Lydia Donahue, who was ten years his senior. The couple had no children.74

Thomas Phillips was recorded as living in Arkansas in 1937.75

Notes

Mollie Smith.

1) Austin Daily Statesman, January 1, 1885, January 2, 1885.

2) U.S Census, McClennan County, Texas, 1880.

3) Austin Daily Statesman, January 1, 1885, January 2, 1885. Austin City Directory 1881, 1883, 1885.

4) U.S Census, McClennan County, Texas, 1900.

5) U.S. Census, Travis County, Texas, 1900. U.S. Census, Cook County, Illinois, 1910, 1920, 1940. Austin City Directory, 1895, 1903.

6) U.S. Census, Travis County, Texas, 1900. Austin City Directory, 1897-1922.

7) Ibid.

Eliza Shelley

8) Austin Daily Statesman, May 8, 1885.

9) Austin Daily Statesman, May 8, 1885. Austin City Directory, 1885. U.S. Census, McLennan County, Texas, 1880.

10) Austin Daily Statesman, May 8, 1885. Austin City Directory, 1885. U.S. Census, McLennan County, Texas, 1880. U.S. Census, Travis County, Texas, 1880.

11) Austin Daily Statesman, May 8, 1885. Austin City Directory, 1885.

12) U.S. Census, Walker County, Texas, 1880. Conduct Registers, Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Huntsville, Texas. Austin, Texas: Texas State Library and Archives Commission.

13) U.S. Census, McLennan County, Texas, 1880. U.S. Census, Travis County, Texas, 1900, 1920. Austin City Directory 1906.

14) U.S. Census, Tarrant County, Texas 1910. Texas Death Certificates 1903-1982 Online Database.

15) U.S. Census, McLennan County, Texas 1880. San Angelo City Directory, 1944.

Irene Cross

16) Austin Daily Statesman, May 23, 1885.

17) U.S. Census, Travis County, Texas, 1870.

18) U.S. Census, Travis County, Texas, 1880.

19) Austin Daily Statesman, May 23, 1885. Austin City Directory, 1885.

20) Ibid.

21) Record of Internments, Oakwood Cemetery, City of Austin, Texas.

22) U.S. Census, Travis County, Texas, 1870, 1880, 1900, 1910. Marriage Records, Travis County District Clerk, Austin, Texas. Austin City Directory, 1887, 1918.

23) Ibid.

24) U.S. Census, Travis County, Texas, 1870, 1880, 1900, 1910, 1920, 1920. Austin City Directory, 1922, 1927, 1929, 1936, 1939, 1955, 1957, 1958. Texas Death Certificates Online Database.

Mary Ramey

25) Austin Daily Statesman, September 1, 1885.

26) U.S. Census, Travis County, Texas, 1880.

27) U.S. Census, Travis County, Texas, 1870, 1880. Austin City Directory, 1881, 1883, 1885. Jennifer Bridges, “Carrington, Edward H.” Handbook of Texas Online.

28) Ibid.

29) Ibid.

30) U.S. Census, Travis County, Texas, 1900.

31) Marriage Records, Travis County District Clerk. Austin, Texas.

32) U.S. Census, Travis County, Texas, 1900. Jennifer Bridges, “Carrington, Edward H.” Handbook of Texas Online.

33) U.S. Census, Travis County, Texas, 1870, 1880, 1900, 1910.

34) Record of Internments, Oakwood Cemetery, City of Austin, Texas.

Gracie Vance & Orange Washington

35) Austin Daily Statesman, September 29, 1885. San Antonio Express, September 28, 1885.

36) Austin Daily Statesman, September 29, 1885. San Antonio Express, September 28, 1885. Austin City Directory, 1885.

37) U.S. Census, Washington County, Texas, 1870.

38) U.S. Census, Travis County, Texas, 1880. Marriage Records, Travis County District Clerk, Austin, Texas.

39) U.S. Census, Travis County, Texas, 1880. Austin City Directory, 1914.

Susan Hancock

40) Austin Daily Statesman, December 25, 1885.

41) U.S. Census, Washington County, Texas, 1870. U.S. Census, McLennan County, Texas, 1880.

42) U.S. Census, Haywood County, Tennessee, 1850. U.S. Census, Fannin County, Texas, 1860. U.S. Census, Washington County, Texas, 1870. U.S. Census, McLennan County, Texas, 1880.

43) Texas, Confederate Pension Applications, 1899-1975. Vol. 1–646 & 1–283. Austin, Texas: Texas State Library and Archives Commission.

44) U.S. Census, Washington County, Texas, 1870

45) U.S. Census, McLennan County, Texas, 1880.

46) Austin Daily Statesman, December 25, 1885; December 30, 1885; January 29, 1886; January 30, 188;, February 5, 1886; June 5, 1886; June 18, 1886; June 19, 1886; June 22, 1886; June 1, 1887; June 2, 1887; June 3, 1887; June 8, 1887; New York Times, December 26, 1885. San Antonio Express, December 26, 1885.

47) Ibid.

48) Ibid.

49) Austin Daily Statesman, June 19, 1886.

50) Ibid.

51) Austin Daily Statesman, June 8, 1887.

52) Texas Death Indexes, 1903-2000. Austin, TX, USA: Texas Department of Health, State Vital Statistics Unit.

53) Marriage Records, Travis County District Clerk, Austin, Texas. Austin City Directory, 1885. Austin Daily Statesman, December 22, 1886.

54) Marriage Records, Travis County District Clerk, Austin, Texas. Austin City Directory, 1900. U.S. Census, Travis County, Texas, 1900.

55) Ibid.

56) Austin City Directory, 1903.

57) Waco City Directory, 1909. U.S. Census, McLennan County, Texas, 1910, 1920. U.S. Census Dallas County, 1930, 1940. Texas, Death Certificates, 1903–1982 Online Database.

58) Personal interviews with Richard Bagby, Scherrie Osborn.

59) Waco City Directory, 1886. Marriage Records, Travis County District Clerk, Austin, Texas. U.S. Census, Travis County, 1900. U.S. Census, Hawaii Territory, 1920. The Typographical Journal, 1914. Honolulu Star Bulletin, Aug. 7, 1912; Aug. 8, 11, 1913; Mar. 17, 1914.

60) Austin City Directory 1887, 1897.

Eula Phillips

61) San Antonio Express, December 26, 1885. Austin Daily Statesman, February 14, 1886. New York Times, December 26, 1885.

62) U.S. Census, Travis County, 1870, 1880. Eanes, Richard. The Descendants of Edward Eanes of Henrico and Chesterfield Counties in Virginia. 1940. Slaughter-Eanes Papers, 1835-1944. Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin. Heep, Zoe Cage, Zoe’s Story. Austin, Texas : 1984. Personal interviews with Dorothy Larson, Marilyn McLeod, Pat Tarpy, Betsy Urban.

63) U.S. Census, Travis County, 1870.

64) U.S. Census, Travis County, 1880. Austin Weekly Statesman, July 21, 1881.

65) Austin Daily Statesman, December 1882. Travis County Civil Minutes, Vol. O, 1882-1883.

66) Marriage Records, Travis County District Clerk, Austin, Texas.

67) And previous paragraphs: Austin City Directory, 1885. U.S. Census, Travis County, 1880. Austin Daily Statesman, December 25, 1885; December 31, 1885; February 13, 1886; February 14, 1886; February 16, 1886; May 26, 1886; May 27, 1886; May 28, 1886; May 30, 1886; October 22, 1886; November 11, 1886. San Antonio Express, December 26, 1885; February 14, 1886; February 26, 1886; May 30, 1886. The State of Texas vs. James O. Phillips. Travis County Archives.

68) Ibid.

69) “James O. Phillips vs. The State.” Reports of Cases Argued and Adjudged in the Court of Appeals of Texas. 1883-1889. Austin : Hutchings Printing House.

70) Austin City Directory, 1887. U.S. Census, Williamson County, 1900, 1910, 1920. Texas, Marriage Collection, 1814-1909 Online Database. Texas Death Indexes, 1903-2000. Austin, TX, USA: Texas Department of Health, State Vital Statistics Unit.

71) Ibid.

72) U.S. Census, Travis County, Texas, 1900. Austin City Directory, 1906. World War I Selective Service System Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration. Texas Death Certificates 1903-1982 Online Database. Galveston City Directory, 1921.

73) Ibid.

74) Ibid.

75) Thomas Phillips date of death was previously listed as 1920, however this subsequently proved to be incorrect. Social Security records list him as living in Arkansas in 1937.

Images:

Photo-illustration from unidentified albumen print.

Detail from U.S. Census, McLennan County, Texas, 1880.

Mary Ramey photo illustration from unidentified tintype.

Lena Hancock. Dallas, 1955. Courtesy of Scherrie Osborne.

Galveston Causeway Postcard.