I am not the first to delve into this mystery. The first time I opened the drawer of the microfilm cabinet and saw all the small cardboard boxes of microfilm packed snuggly inside, I noticed that the boxes labeled 1885 were noticeably more worn than any of the others, undoubtedly having been pulled out, opened and put back many times before I got to them. I wondered who had looked at them and what they had found.

What was I looking for? The details of a murder mystery that drew comparisons to Jack the Ripper – someone stalking through the night with an axe, committing horrifying crimes and disappearing without a trace. I was surprised such a sensational story did not have more notoriety; I myself had read only the briefest mentions of it. A lot of Old West history is long on story but short on facts, filled with colorful characters and events and I wondered if this was just another Texas Tall Tale, an exaggeration from the imaginations of old-timers to scare the kids around the campfire. Why had these murders remained a mystery? And could a close examination of the facts shed any light on the subject?

When I first asked at the Austin History Center in 1996, I was told there had been a clipping file about the murders but that it had been missing for some time. I suppose if those newspaper clippings had been available I might not have pursued this as thoroughly as I did. Over the course of about a year, I gradually assembled my own files on the murders, taking lots of notes and making lots of photocopies and with a lot of patience and persistence I was able to somewhat satisfy my curiosity about the crimes, and discover the who what when and where. But even now there are many questions about the murders that may never be answered. My intention in sharing what I’ve found, collected and published is to hopefully present it with some clarity so that others who are interested can perhaps make some heads or tails of it and maybe offer new insights and ideas.

The main problems I encountered with this murder-mystery-as-research project were the lack of extant sources, a lack of indexing for the sources that were available, and the difficulty of deciphering old newspaper microfilm, all of which I believe would have been major impediments to any casual reader or would-be researcher.

The lack of extant sources is probably due in part to the 1880s being something of a lull in Texas history. Materials from prior historical eras of Texas including, The Republic, The Civil War and Reconstruction, and the Old West have been vigorously collected and archived and there is much accompanying scholarship. Materials from the 1880s and 1890s are scarce by comparison and interest and enthusiasm for Texas history does not pick up again until the Oil Boom at the turn of the century.

Thankfully the Austin History Center’s collections and their cataloging and indexing are superb, and if their resources had not been put in place long ago and maintained by dedicated and conscientious professionals and volunteers this project would have been much more difficult. And with increasing efforts to digitize collections I expect there will be many new and interesting discoveries made.

With that in mind I want to briefly describe some of what was involved in my research, some of the sources I used, and I also want to give thought to the way the murders of 1885 have been remembered.

William Sydney Porter famously mentions the servant girl annihilators in an 1885 letter, later included in the O.Henry short story compilation, Rolling Stones, published 1912. Had that letter not been reprinted the crimes might have been completely forgotten.

In Mary Starr Barkley’s History of Travis County and Austin, published 1963, she briefly mentions the murders as part of local folklore:

..the axe murderer who made citizens nervous in 1884-1885. His victims were women, always killed while sleeping. No one knows, even today, who murdered the thirteen people, with the last murder being on Christmas, 1885.

Even though the details as remembered by Barkley are incorrect, it is remarkable to see how the memory of the crimes, as a story retold over the years, eventually took on the aura of a local legend, not unlike the Whitechapel murders of 1888 which continued to fascinate Londoners in subsequent decades.

In 1983 the murders were mentioned by David C. Humphrey, LBJ Library archivist, in an article in Southwestern Historical Quarterly. He gets the details substantially correct and cites specific Austin Daily Statesman sources:

…six black Austinites, five of them females, were viciously attacked at night, in all but one case with axes and knives. More than one victim was raped. None of the murders was solved, despite efforts of specially hired detectives. Then on Christmas eve two white women who live a dozen blocks apart were dragged from their beds into their backyards, at least one of them raped, and both butchered to death with axes. There were no suspects.

Those three brief mentions by Porter, Barkley and Humphrey were the only descriptions of the murders that found their way into print in the 100 years since the murders had been committed. (Although Humphrey’s account was subsequently re-tooled for inclusion in various Austin city guidebooks.)

I had started my search for information about the murders by searching the index of the Austin American-Statesman, which at the time was available on an old-fashioned terminal station in the Austin History Center. The Statesman index did not include the late 19th century and no entries about the murders were to be found from the 20th century. Searches of various academic indexes for any mention of the murders turned up nothing. A complete lack of secondary sources meant going directly to primary sources, in this case, 19th century newspapers. Since Austin newspapers from that time period were not indexed there would be no easy way to find what I was looking for. I simply had to start reading without knowing where to start.

There were several daily and weekly newspapers published in Austin during the 1880s but only the Austin Daily Statesman has survived in completeness in archived microfilm to the present day. Microfilm is not the most user-friendly format to work with but at least it is easily stored and preserved and in many cases it is the only format available when brittle print originals have long since turned to dust.

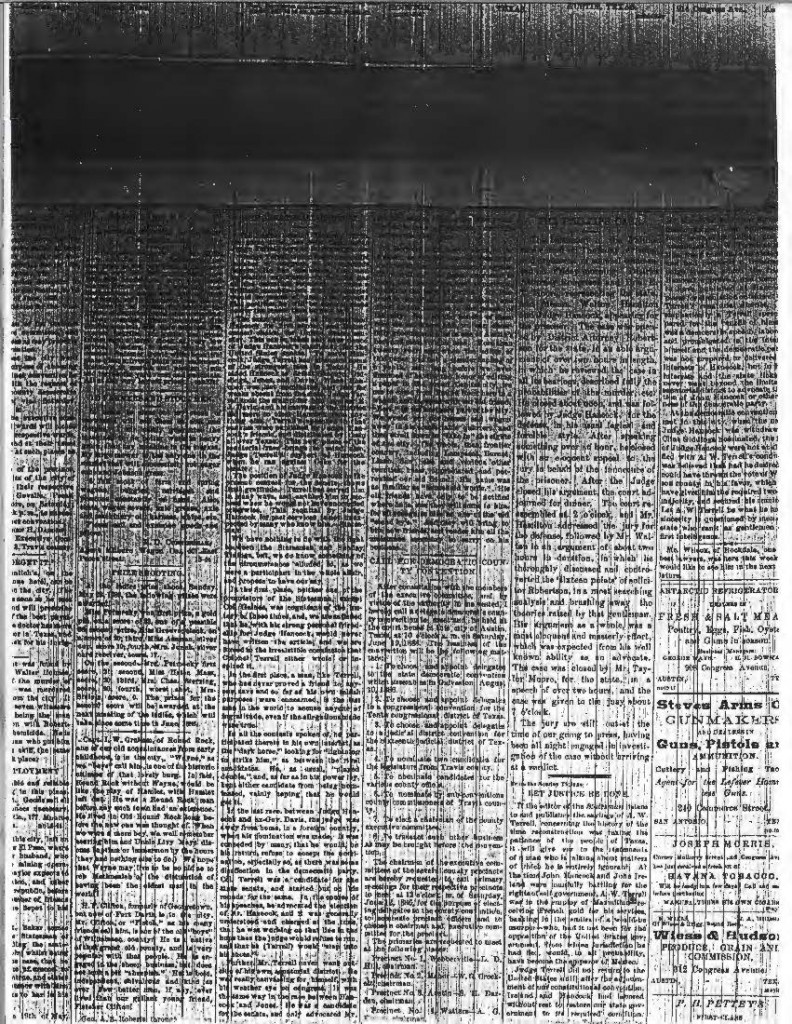

The Austin Daily Statesman provided its readers with typical coverage of politics, business, and sports in central Texas as well as national and international news and I would assume its readership was well-informed. But the 1880s Statesman packed as much information as possible into the smallest number of column inches and its layout was an amalgamation of news, advertisements and local gossip, with no clear delineation between them, all set in a tiny font face. I have read plenty of microfilm but reading the often poorly photographed 19th century newsprint proved to be difficult on the eyes and I doubt my now middle-aged eyes would be up to the task.

Austin Daily Statesman Microfilm. Not all of it was this bad, but this is an example of some of the worst.

Most of my microfilm reading was done at the Briscoe Center for American History (formerly the Barker Texas History Center) because their extensive collection of Texas newspapers in one convenient location made it possible to easily compare the way the murders were reported (if they were reported at all) in other cities. The San Antonio Express, the major newspaper of the closest large city, often provided important coverage of the murders.

Eventually I did find the beginning of the story. I carefully read every issue of the Statesman, not wanting to miss any detail as the crime spree unfolded throughout 1885; I read about the continued confusion after the last murders and the wild accusations and prosecutions in 1886, and when I thought I wouldn’t find anything else I found the surprising conclusion in the summer of 1887.

Although the story of the murders did not tie up into a neat narrative package, I had an outline, a timeline and a cast of characters that I was anxious to find out more about.

None of the persons directly involved in the murders were well-known, influential or historically prominent. Most of the victims, the servants and their families, were from the lower strata of society; the last two victims, Susan Hancock and Eula Phillips were at best middle-class, their names were not among those family names which normally appeared in the daily happenings of Austin’s who’s who. By comparison, some of those frequently suspected and accused in the murders were sometimes infamous for their criminal records and accounts of their misdeeds were often described in very memorable and colorful language.

Contemporary (1880s) biographical information (and by that I mean personal detail beyond name and occupation) about city officials, police officers and others who worked in an official capacity at the time was scarce excepting those most prominent.

Common sources of biographical information for ordinary citizens in the late 19th century are census records, family papers and letters, church records, city directories, birth indexes, death indexes, all of which I used with varying degrees of success to find any personal details I could.

The Austin History Center has extensive collections of historic papers from some of Travis County’s earliest settlers and most prominent families. I examined several family papers collections including the Hornsby and Von Rosenberg papers hoping to find any offhand mention of the crimes, as with the Porter letter, but unfortunately I did not find any documents or ephemera directly related to the 1885 murders in any of the family papers collections I examined.

I made frequent visits to the Texas States Library and Archives to use their extensive United States census archives (now conveniently online, but when I was doing my research it was still microfilm only). The State Archives is especially popular with genealogists and it was always busy. Genealogists are a helpful bunch, very collaborative, and I gratefully remember their assistance deciphering handwritten census entries, teaching me some of the tricks and showing me how patient you have to be if you’re going to find what you’re looking for.

It was fascinating to browse through the 1880 Travis county census and come across names that were familiar from the 1885 newspaper stories; to see where they had lived and with whom; although by 1885 many were already in different locations and in different occupations.

One of the most striking things I discovered was that everyone was much younger than I expected; the victims, the suspects, even the police and city officials were frequently in their 20s. When I read the newspaper accounts I had envisioned hard, old, grizzled law men, but the relentless Justice William Von Rosenberg was only 25 years of age; ex-Texas Ranger James Lucy was 31; the undauntable Police Sergeant John Chenneville was the elder at 44.

I was also surprised to discover how communal Austin households were in the 1880s. The census records revealed it was common for households to have extended families with several generations living together under one roof, often with servants, sometimes renting a room to a boarder as well. The employment of domestic servants was common among Austin households and was not something that would denote their employers being wealthy or upper-class as it generally would these days.

***

In the late 19th century, investigations and prosecutions of serious crimes were not without flaws but they were methodical. In the servant girl murder cases there were arrests, evidence was gathered, and trials were held. I was surprised to find that there were legal artifacts from that time period still intact including some police and court records.

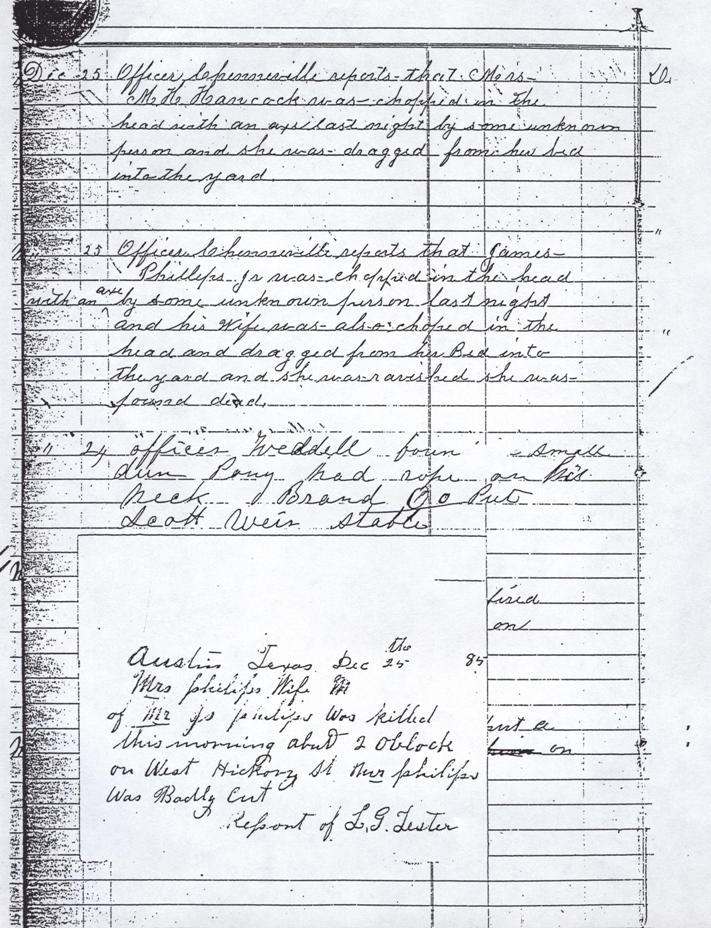

The most fascinating items I came across were the original Police Calls and Arrests ledgers from the 1880s. These volumes are a treasure trove of demographic information with details for minor crimes such as swearing and spitting to the much more serious. The ledgers themselves are wonderful, physical artifacts in amazingly good condition and I remember worrying the frail, ancient woman at the Austin History Center who retrieved the volumes for me was going to be crushed by the substantial leather-bound tomes. The Police Calls ledger contains entries recorded by the police clerk at the time the crimes were reported.

page from 1885 Police Calls Volume, AR.P.01, Laws Collection, Austin History Center, Austin Public Library.

Turning the pages and reading those hand-written entries describing the murders is close as one can get to those mysterious events so long ago.

I was disappointed by the lack of photographic materials, but there was no mention of anything like crime scene photos having been taken at the time. One thing I hoped to find was a photograph of a bullet specifically mentioned as having been photographed in 1886 in connection to the murders. I tried to imagine where it might have ended up but I was unable to find it; it is probably long gone, or if it still exists it is perhaps in a medical archive somewhere.

One of the most valuable resources I came across, not only for this project but for anyone wanting to utilize local history resources was the Inventory of County Records, Travis County Courthouse, Austin, Texas (now available online). The Inventory provides collection-level catalog descriptions of historical materials and confirms their physical location, which is very important in instances where the records are so old and so infrequently accessed that their caretakers may not even know they exist.

According to the Inventory, criminal court minutes from 1885 were located at the office of the Travis County District Clerk. With photocopies of that documentation I went to the Travis Country Courthouse and found myself once again sitting in front of a microfilm reader. The staff of the District Clerk office, who had never had the occasion to dig out that particular reel of microfilm, were surprised by the request, but it was there waiting in the back of a filing cabinet. The Criminal Minutes microfilm contains photographs of ledger entries containing rudimentary information about court cases and their disposition, but there is nothing resembling trial transcripts. The only thing that resembles a trial transcript is the case of James O. Phillips vs. The State, published in Reports of Cases Argued and Adjudged in the Court of Appeals of Texas. The published report goes into great detail regarding the Phillips case, especially the testimonies regarding the turbulent relationship between Eula Phillips and her husband and immediate family, and it reads like a lurid novel.

***

After The Servant Girl Murders was published I had the pleasure of meeting Eula’s great-grand-niece, who shared some of her family history with me, including the fact that her great-grandmother, Alma, who lived into the 1950s, had never mentioned the murders to her while she was alive. Obviously the murders were not something one forgets, or forgets to mention, but I imagine the topic was kept in the closet so to speak, as inappropriate subject matter for a child. But I also imagine serial rape and murder were not the subjects of polite conversion in general, and especially not during the first half of the 20th century.

Most of the early local histories of Austin that I’ve read (there are many unpublished manuscripts and pamphlets in the AHC collections) have been written by amateur local historians such as Barkley, and they place a strong emphasis on progress, look how far we’ve come, and the inherent goodness in all things Texan, Southern and Austin. The darker aspects of 19th and early 20th century history are diminished in these histories and usually not mentioned at all. The most violent periods of Texas history – including most of the 19th century, the Frontier, Civil War, Reconstruction — are all replete with deprivation, depravity and unpredictability, but those histories are in sense redeemed by recording demonstrated examples of heroism, patriotism, sacrifice and progress. The servant girl murders were a barbarism from that violent and still near past but without any accompanying narrative of justice, heroism, or even rational explanation, and they were still fresh in the minds of many who had lived through them and they were anxious to leave them behind. And so the murders did not see mention in print until almost a century later.

***

As time passed the memories of the murders were left behind. Those who were literally left behind, the women, the girls, the mothers who did not survive that fateful year were laid to rest in the Austin City Cemetery (later renamed Oakwood), located on the northeastern outskirts of 19th century Austin.

I visited Oakwood Cemetery several times to look for the names I had read so much about. I had become engrossed with a brief, violent sliver of their lives, but I did not know much more about them. For most, their names found their way into the news due to tragic circumstances and then they receded into obscurity with the passage of time. I wondered about those who left Austin, what fortunes they had found; and those who stayed, were they able to put the past behind them and prosper?

Only one victim’s grave is marked. None of the graves of the African-American victims are marked; they are only listed as having been buried in “colored grounds”, an unmarked expanse of grass near the western gate.

Eula’s name is listed in the cemetery index as Luly, her last resting place in the “old grounds” is not specified. I wondered if she had been somewhat disowned in death by her family; there is no evidence of a marker for her grave ever having been put in place.

Many of the women who were killed that year were frequently subjected to unfair characterizations after their death by those who were ready to cast blame upon the victims as having been unvirtuous and having brought misfortune upon themselves, a sense that these women were different and it’s a shame but what do you expect.

Even in the aftermath of the last two murders, more critical opinions were voiced (though the victims were married, white women) as to how the victims and their families conducted their affairs, and their personal lives were subjected to intense scrutiny in the press.

Susan Hancock is the only victim whose grave has a headstone. The stone has fallen over; the inscription side is facing upwards. It is carved with the memorial “Tho’ lost to sight to memory dear,” and the word “MOTHER” is at the head of the stone, which leads me to believe that it was commissioned and placed there by her surviving daughter many years afterwards, as she would have been too young and without means to do so earlier. The inscribed year of her death, 1884, is inaccurate, which leads me to believe that some time had passed before the stone was placed there.